July 23, 2010 – June 13, 2012

Educator Exhibition Resource

About this Guide

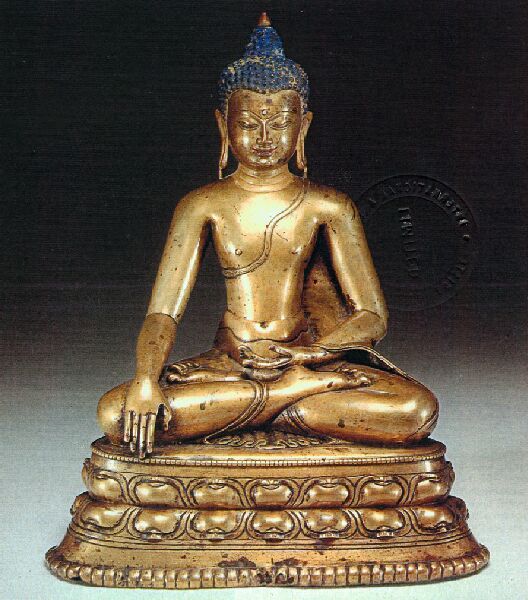

Buddha Shakyamuni

Bodhisattvas (Green Tara)

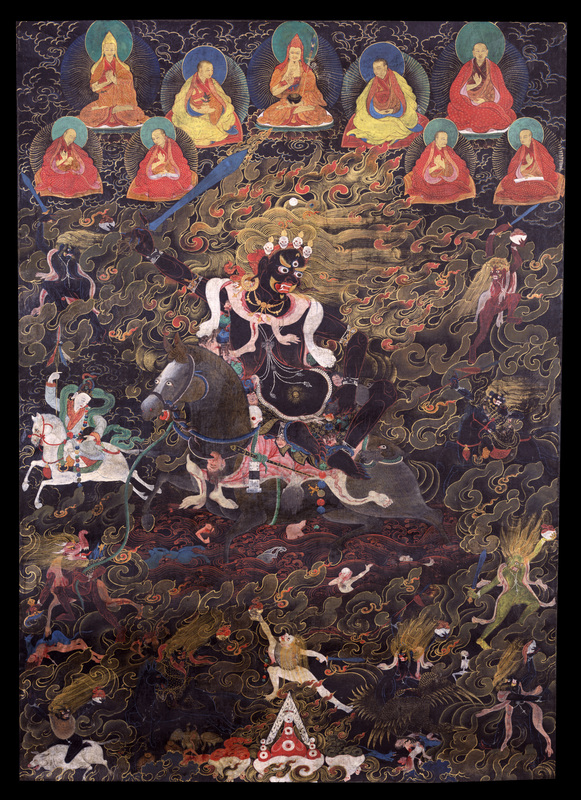

Wrathful Deities (Shri Devi)

The Tibetan Shrine Room

Resources for Further Learning

Download this Guide (PDF)

About this Guide

The discussion questions, responses, and resources that follow are intended to enhance your experience of the exhibition, Gateway to Himalayan Art. The exhibition provides an introduction to the art and sacred traditions of the Himalayan region, and is divided into five thematic sections: The Map; Figures and Symbols; Materials and Techniques; Purpose and Function; and the Tibetan Shrine Room. These sections provide opportunities for you and your students to explore the geography, principal figures, materials, and ritual function of Himalayan art.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

1. The Map

The Himalayan region covers a vast swath of territory over 1600 miles long. Home to the highest mountain in the world, Mt. Everest, this region has experienced tremendous shifts of population, political allegiances and boundaries over the millennia. As information and ideas passed along trade routes, cultures of stunning diversity and complexity developed.

Discussion question: How might the geographical information provided on the map help to explain the cultural diversity and complexity of the Himalayan region?

Discussion response: The towering peaks of the Himalayan mountain range and Tibetan Plateau have thwarted political and economic cohesion in the region but also have created rich pockets of cultural diversity.

Tibet; 1200 -1299; Metal, Gilt Copper Allow with Pigment; Collection of Rubin Museum of Art

Buddha

The term buddha, meaning “awakened” or “enlightened,” was first used to refer to Shakyamuni, who lived some time between the sixth and fourth centuries BCE in northern India and whose teachings became the foundation of Buddhism. Shakyamuni became the Buddha by achieving enlightenment, or a complete understanding of the true nature of reality, which freed him from the endless cycle of birth, death, and rebirth. Over time “buddha” came to refer to not only one person but all manifestations of enlightenment. Buddhas are said to possess distinct marks that are often shown in their representations, most notably a cranial protuberance (ushnisha), a tuft of hair between the eyebrows (urna), and long earlobes, and they are usually shown wearing the robes of a monk.

Discussion question: The Buddha Shakyamuni is traditionally depicted with distinctive physical features and gestures that tell the story of his spiritual awakening (enlightenment). Can you identify them?

Discussion Response:

- Earth-touching mudra: When the Buddha attained a spiritual awakening, he touched the earth to witness it. This mudra (gesture) represents the moment when Siddhartha Gautama, who was once a Hindu prince, became the Buddha.

- Ushnisha: According to tradition, when the Buddha became enlightened, a cranial protuberance grew at the top of his head because the size of his brain increased.

- Urna: The tuft of hair between the eyebrows illustrates radiant wisdom.

- Long earlobes: When Siddhartha was a young Hindu prince, he wore heavy earrings that stretched his earlobes.

Bodhisattvas and Tantric Deities

Bodhisattvas are beings who aspire to attain the awakened state of a Buddha and help others to achieve this state as well. Peaceful and compassionate, they take a vow to end all suffering. Bodhisattvas can be male or female and usually wear crowns, jewelry, and fine garments of Indian royalty. When bodhisattavas assume a female form, they are often referred to as female deities.

Green Tara

Tibet; 1700-1799; Ground Mineral Pigment, Raised Gold on Cotton; Collection of Rubin Museum of Art

The large central figure in this painting represents Green Tara. Tara is one of the most beloved deities in Himalayan and Central Asian Buddhist traditions. Known as the “savioress,” she protects travelers from danger and provides comfort from fear. In this painting, Tara sits on a lotus petal throne and is surrounded by lush flowers and plants. In Buddhist iconography, green is the color of growth, vitality, and movement

Tantric or Wrathful Deities

Tantra is an ancient Indian spiritual system of ritual practices that was incorporated into Tibetan Buddhism. In Tantric Buddhist tradition there exist wrathful deities who appear frightening and demonic but are, in fact, powerful helpers and protectors who assist the practitioner to transform into a Buddha. Tantric deities—the indispensable subjects of Himalayan art—are the focus of esoteric religious practices (tantras) that aim to radically transform conventional understandings of reality. Tantric deities and practices are as diverse as people’s needs and capacities. Female and male deities in embrace represent the unity of wisdom (understanding of reality) and method (compassionate action), two aspects of the enlightened mind. Tantric deities can have multiple heads, arms, and legs, symbolizing their many abilities.

Shri Devi, Dorie Rabtenma

Tibet; 1600-1699; Ground Mineral Pigment, Fine Gold Line, Black Background on Cotton; Collection of Rubin Museum of Art

The central figure in this painting is Shri Devi, a wrathful female protector of Tibet. Astride a horse, she is colored black, clutches a sword, and is surrounded by flames. In Buddhist iconography, black symbolizes a fierce, unrelenting determination to accomplish all goals.

Discussion question: Looking at the two paintings of Green Tara and Shri Devi, how might an observer distinguish a bodhisattva from a tantric wrathful deity? Describe differences and similarities between the two paintings.

Discussion response: The plants surrounding Tara, as well as the flowers she holds and her gentle expression, evoke a sense of calm and ease, whereas the flames, smoke, and blackness surrounding Shri Devi create a sense of mystery and power.

This section of the exhibition presents religious art in context. The installation features religious artifacts as they would be displayed in the domestic shrine of a wealthy Tibetan Buddhist. The objects are from the collection of Alice Kandell, who designed a shrine room in her New York City apartment to closely resemble Tibetan Buddhist shrines she encountered in her travels. All of the objects—scroll paintings as well as sculptures of buddhas, bodhisattavas, tantric deities, female deities, wrathful deities and teachers—have been arranged on traditional Tibetan furniture and according to the hierarchy they assume in Tibetan Buddhist practices.

Discussion question: On the central altar there is a sculpture made of silver, about two feet high. Who does it represent? Why would this figure have been placed in the middle of the altar?

Discussion response: This sculpture represents Buddha Shakyamuni in the earth-touching mudra, as seen in the earlier sculpture of the Buddha. Unlike the other sculptures in the shrine, this one was made from silver repoussé (hammered metal) and still retains its handsome base and beautiful flower mandorla background behind the Buddha (for more information, refer to A Shrine for Tibet, p. 71).

Resources for Further Learning

www.rmanyc.org/gateway

Gateway to Himalayan Art//Explore exhibition resources to further discover the principal concepts of Himalayan art through interactive multi-media and didactic materials.

www.rmanyc.org

The Rubin Museum of Art//Explore Multimedia resources and videos to find out about present and upcoming exhibition and programs at the Rubin Museum of Art.

www.exploreart.org

Explore Art// Journey behind works of Himalayan art on this interactive site, revealing the stories, ideas and beliefs that inspired them. The site also lets visitors consider how peoples of other culture have expressed ideas on similar issues through their own artistic traditions.

www.himalayanart.org

Himalayan Art Resources//Search a virtual museum of documented Himalayan art that includes high-resolution images, essays, articles, thematic collections, bibliographies, and activities for children.

www.tibetanlineages.org

Treasury of Lives: Biographies of Himalayan Buddhist Masters//Browse biographies and portraits of Tibetan Buddhist and Bon masters by religious tradition, geography, community, and historic period.

Recommended Readings

- Beer, R. The Handbook of Tibetan Buddhist Symbols. Boston: Shambhala, 2003.

- Eck, D. Darśan: Seeing the Divine Image in India. New York: Columbia University Press, 1998.

- Eliade, M. Yoga: Immortality and Freedom. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003.

- Jackson, D. & J. Jackson. Tibetan Thangka Painting: Methods and Materials. Ithaca, N.Y.: Snow Lion Publications, 2006.

- Laird, T. The Story of Tibet: Conversations with the Dalai Lama. New York: Gove Press, 2006.

- Leidy, D. P. “The Buddha Image: 2nd to 7th Century,” The Art of Buddhism: An Introduction to its Meaning and History. Boston: Shambhala, 2008: 31-55.

- Lopez, D.S. Editor. Buddhism in Practice. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995.

- Powers, J. Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism. New York: Snow Lion Publications, 2007.

- Rhie, M. & R. Thurman. A Shrine for Tibet: The Alice S. Kandell Collection. New York: Tibet House US, 2009. Strong,

- J.S. The Experience of Buddhism. Belmont, C.A.: Wadsworth, 1995.

- Trungpa, C. Cutting Through Spiritual Materialism. Boston: Shambhala, 2002.