June 27, 20112 – June 3, 2013

Educator Exhibition Resource

Figures and Symbols

Buddha Shakyamuni

Bodhisattvas

Tantric Deities

Materials and Techniques

Hollow Metal Casting

Purpose and Function

Ritual (Vajra & Bell)

Secular Gains

Black Jambhala

Tara, Mother of All Activities

Wheel of Existence

The Tibetan Shrine Room

Resources for Further Learning

Download this Guide (PDF)

ABOUT THIS GUIDE

The introduction, discussion questions and responses, and resources that follow are intended to enhance your students’ understanding of the exhibition, Gateway to Himalayan Art. The exhibition provides an introduction to the art and sacred traditions of Nepal, Tibet, Bhutan, Northern India, Mongolia, and Western China.

Introduction

Gateway to Himalayan Art identifies the geography, principal figures, materials, ritual practice, and contextual setting of the sacred traditions of the Himalayan region through five thematic sections: The Map; Figures and Symbols; Materials and Techniques; Purpose and Function; and The Tibetan Shrine Room.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

Map of Himalayas

The Himalayan region covers a vast swath of territory over 1600 miles long. Home to the highest mountain in the world, Mt. Everest, this region has experienced tremendous shifts of population, political allegiances and boundaries over the millennia. As information and ideas passed along trade routes, cultures of stunning diversity and complexity developed.

Discussion question: How might the geographical information provided on the map help to explain the cultural diversity and complexity of the Himalayan region?

Discussion Response: The towering peaks of the Himalayan mountain range and Tibetan Plateau have thwarted political and economic cohesion in the region but also have created rich pockets of cultural diversity.

Exploratory Discussion: The map was designed to provide borders for some countries located within the Himalayan region, such as Nepal and Bhutan, while other regions, such as Tibet and Kashmir, are indicated by name only but do not have distinct borders. Why do you think the map was designed this way?

FIGURES AND SYMBOLS

This section identifies the key figures and symbols in Himalayan sacred traditions, in particular, Buddhism, a 2500 year-old belief system that developed in northern India.

Buddha

The term buddha, meaning “awakened” or “enlightened,” was first used to refer to Shakyamuni, who lived some time between the sixth and fourth centuries BCE in northern India and whose teachings became the foundation of Buddhism. Shakyamuni became the Buddha by achieving enlightenment, or a complete understanding of the true nature of reality, which freed him from the endless cycle of birth, death, and rebirth. Over time “buddha” came to refer to not only one person but all manifestations of enlightenment. Buddhas are said to possess distinct marks that are often shown in their physical representations, and they are usually shown wearing the robes of a monk.

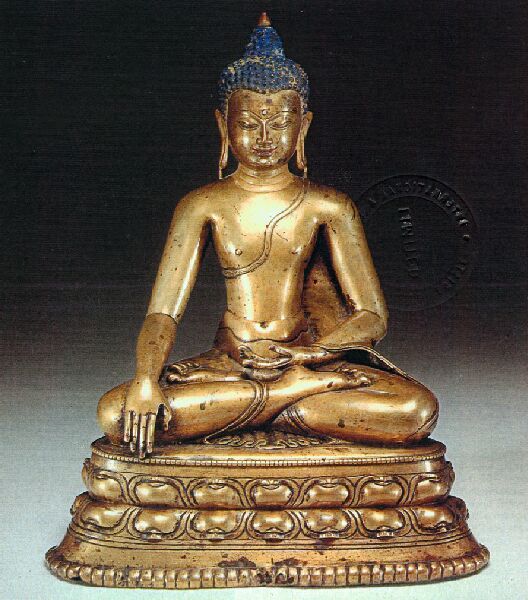

The figure in this sculpture represents the Buddha Shakyamuni, “The sage of the Shakya clan,” who lived in the late 6th c. B.C.E., and had a profound awakening while meditating under the Bodhi tree.

Discussion question: The Buddha Shakyamuni is traditionally depicted with distinctive physical features and gestures that tell the story of his spiritual awakening (enlightenment). Can you identify them?

Discussion response:

- Earth-touching mudra: When the Buddha attained a spiritual awakening, he touched the earth to witness it. This mudra (gesture) represents the moment when Siddhartha Gautama, who was once a Hindu prince, became the Buddha.

- Ushnisha: According to tradition, when the Buddha became enlightened, a cranial protuberance grew at the top of his head because the size of his brain increased.

- Urna: The tuft of hair between the eyebrows illustrates radiant wisdom.

- Long earlobes: When Siddhartha was a young Hindu prince, he wore heavy earrings that stretched his earlobes.

Exploratory discussion: The throne of double lotus flowers beneath the Buddha indicates that he is an enlightened being. Can you find other examples of lotus petal thrones in the gallery? In what ways are they similar to and/or different from each other?

Bodhisattvas

Bodhisattvas are beings who aspire to attain the awakened state of a Buddha and help others to achieve this as well. Peaceful and compassionate, they take a vow to end all suffering. Bodhisattvas can be male or female and usually wear crowns, jewelry, and fine garments of Indian royalty. When bodhisattavas assume a female form, they are often referred to as female deities.

Suryabaskara

This painting depicts a male bodhisattva, Suryabaskara, whose name means “the Sun’s Rays.” He holds a white lotus flower in his hand while standing on a lotus petal disc.

Discussion Question: How does this painting reflect the inner peace and infinite compassion of a bodhisattva?

Discussion Response:

- Suryabaskara’s gentle expression and elegant and graceful body reflect a sense of inner peace.

- The lotus symbolizes spiritual perfection and Suryabaskara is surrounded by large lotus flowers floating in a deep blue sky.

- The symmetrical design of the painting evokes a sense of calm and balance, as does the soft texture of the white flowers and fluffy clouds.

Exploratory Discussion: Bodhisattvas encourage practitioners to follow in their footsteps through exemplary behaviour. In this case, a male bodhisattva is portrayed as gentle, calm, and compassionate. Why would this type of idealized male figure be important for religious communities and lay societies?

Tantric Deities

Tantra is an ancient Indian spiritual system of ritual practices that was incorporated into Tibetan Buddhism. In Tantric Buddhist tradition there exist wrathful deities who appear frightening and demonic but are, in fact, powerful helpers and protectors who assist the practitioner to transform into a Buddha. Tantric deities—the indispensable subjects of Himalayan art—are the focus of esoteric religious practices (tantras) that aim to radically transform conventional understandings of reality. Tantric deities and practices are as diverse as people’s needs and capacities. Female and male deities in embrace represent the unity of wisdom (understanding of reality) and method (compassionate action), two aspects of the enlightened mind. Tantric deities can have multiple heads, arms, and legs, symbolizing their many powerful abilities.

Chakrasamvara

Chakrasamvara and his consort Vajravarahi are the central figures in the painting below. The couple’s embrace represents the unity of skillful method, personified by Chakrasamvara, wisdom, personified by Vajravarahi.

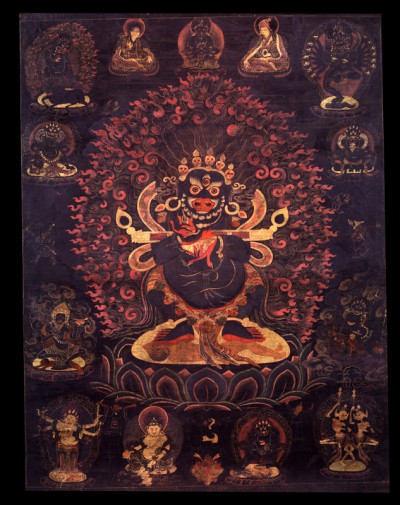

Mahakala Panjarnata

Mahakala PanjarnataTibet; 18th century; Pigment on cloth; Collection of Rubin Museum of Art

The central figure in this painting is, Mahakala, a buffalo-headed tantric deity whose strong body and ferocious expression symbolize an intense and powerful form of wisdom.

Discussion Question: Looking at the two paintings of Chakrasamvara and Mahakala side by side, describe similarities and differences between them.

Discussion Response:

- Similarities: The central figures are surrounded by flames symbolizing the heat of transformative energy; they are standing on lotus petal thrones, indicating that they are enlightened deities; they are vanquishing figures who represent ego attachments by standing on top of them.

- Differences: Chakrasamvara is surrounded by a pastoral landscape and a deep blue sky; they symbolize the vastness of spiritual awareness. Mahakala, by contrast, is positioned in a black landscape. Black is the color of charnal grounds, as well as mystery and the fierce determination to achieve all goals.

Exploratory Discussion:

- Can you name examples of figures found in other sacred traditions and world cultures that remind you of Tibetan Buddhist wrathful deities?

- How might wrathful deities be misinterpreted by people who are not familiar with them?

MATERIALS AND TECHNIQUES

This section addresses the materials and techniques used to create Himalayan sacred art.

Display Case: Hollow Metal Casting of Tara

One method for making religious sculpture in the Himalayas is through a technique called hollow metal casting, a method that thrives in the Himalayas today. This large display case shows how Nepalese artisans have constructed a bronze sculpture of Green Tara in multiple stages.

Discussion Question: After examining the first four steps in the case, focus your attention on the Tara in step 5. What differences do you see between the left and right side of Tara?

Discussion Question: After examining the first four steps in the case, focus your attention on the Tara in step 5. What differences do you see between the left and right side of Tara?

Discussion Response: When the metal sculpture is first removed from the clay mold, the surface is rough. The qualities that give Tara her beauty and vitality, the inlaid jewels, and polished surface of her body, are made during a process called cold chistling.

Exploratory Discussion:

- Tara is gilded (covered with gold) at the end of the sculpting process. What do you think gold symbolizes within a religious context?

- Looking at the sculpture of the standing bodhisattva near Tara’s case, how can you tell that it was made using the hollow metal casting method?

PURPOSE AND FUNCTION

Ritual

This section explores how sacred objects in Himalayan cultures are used in rituals to cultivate generosity, good health, and spiritual awareness.

Display Case: Vajra and Bell, Bhutan circa 20th century, Metal Alloy and Ash Wood.

Although Himalayan art is often appreciated for its aesthetic beauty and fine craftsmanship, the objects in this section are used primarily for ritual practice. The vajra represents skillful method, and the bell signifies wisdom.

Discussion Question: Why might a practitioner hold both of these objects in each hand during a Buddhist ritual?

Discussion Response: When the vajra and the bell are held together, they symbolize the union of skillful method (vajra) and wisdom (bell) within the body and mind of the practitioner.

Exploratory Discussion: Can you name examples of when opposing forces are joined together in other traditions to create a sense of peace, balance, and harmony?

SECULAR GAINS

In Himalayan cultures, religious rituals and the commissioning of sacred art helps practitioners to accumulate merit. Secular forms of merit provide favorable circumstances in life, such as material well-being, good health, and a long life.

Black JambhalaTibet; 13th century; Metalwork; Collection of Rubin Museum of Art

Jambhala is a wealth-bestowing deity. His various attributes symbolize prosperity, such as a large girth and a smiling face. He also holds a mongoose with jewels pouring from its mouth.

Discussion Question: Why is Jambhala’s mongoose disgorging jewels?

Discussion Response: In nature, a mongoose fearlessly attacks and devours poisonous snakes. On a symbolic level, the snake represents avarice. When a mongoose eats a snake, the “poison” of avarice is transformed by the mongoose into gems of generosity. Jambhala and his mongoose bring wealth because they remind people to be generous and to transcend selfishness, which is symbolized by the figure lying beneath Jambhala’s feet.

Exploratory Discussion: Jambhala and his mongoose symbolize how something negative can be transformed into something positive. Can you name other examples of when “poisonous” behaviors and outlooks are transformed into those that are beneficial and life-affirming?

Tara, Mother of All Activities

Tara, Mother of All ActivitiesTibet; 1200 – 1299;Metal, Silver Inlay, Stone Inset: Coral, Turquoise; Collection of Rubin Museum of Art

This sculpture depicts Green Tara, one of the most beloved deities in Himalayan and Central Asian Buddhist traditions. Known as the “savioress,” she protects travelers from danger and provides comfort from fear. Tara extends her right hand in gesture of generosity and protection. She embodies the active feminine aspect of compassion. Whenever her followers recite her mantra (special chant or prayer), it is believed that she will protect them from adversity.

Discussion Question: This Tibetan sculpture of Tara was made eight-hundred years ago, whereas the Nepalese Tara, in the Materials and Techniques section, was made recently. The similarities and differences between the two pieces illustrate both thematic connections and aesthetic diversity across Himalayan cultures. What are some of the similarities and differences?

Discussion Response:

- Similarities: The poses of the two Taras are the same. In both examples, she extends her right foot and right hand to offer help to all those in need, and she holds an utpala flower in her hands.

- Differences: The bodies and facial features of the two Taras are quite different. The Tibetan Tara has a round face, wide eyes, and full–formed body. The Nepalese Tara, in contrast, has a thinner face, a longer, beak-like nose, and a more slender body.

Exploratory Discussion: Tara represents the active feminine aspect of compassion. For her followers, she provides comfort from fear and protects them from danger, including drowning, thieves, fires, false imprisonment, ghosts, and attack by wild elephants, lions, and snakes.

Can you name examples of feminine compassion and protection found in other sacred and/or cultural traditions?

Wheel of Existence

In the Himalayan region, the Wheel of Existence is a popular teaching tool for explaining the cyclic process of life, death, and rebirth (samsara). According to Buddhists, the message of the Wheel of Existence is that the life cycle is repeated over the course of many lifetimes until a practitioner becomes spiritually awakened, providing an escape from these cycles. The six realms below represent the six karmic existences: (1) Hell: Violence (2) Hungry Ghosts: Greed (3) Animals: Ignorance (4) Gods: Pride (5) Demi-gods: Jealousy (6) Human: Selfishness.

The animals at the center of the Wheel of Existence represent three mental “poisons” that create obstacles on the path to enlightenment: the pig symbolizes ignorance; the snake symbolizes anger; and the rooster symbolizes desire.

Wheel of ExistenceTibet; 19thCentury;Ground Mineral Pigment on Cotton Collection of Rubin Museum of Art

Discussion Question: Each quadrant of the Wheel of Existence shows a realm where, from the Buddhist perspective, a person might be reborn. Looking at the bottom quadrant, the Hell realm, how does this realm illustrate the idea of retribution and punishment?

Discussion Response: The scenes of people enduring painful tortures in the Hell realm illustrate the effects of karma: those who commit evil and cruel deeds in the present life will be punished by being reborn in the Hell realm in the next life.

Exploratory Discussion: Yama, the Lord of Death, clutches the Wheel of Existence. A ferocious looking figure, he has a crown of skulls and three bulging eyes, indicating tremendous power and insight. As a teaching tool, why would it be useful to make death look this way?

THE TIBETAN SHRINE ROOM

This section of the exhibition presents religious art in context. The installation features religious artifacts as they would be displayed in the domestic shrine of a wealthy Tibetan Buddhist. The objects are the collection of Alice Kandell, who designed a shrine room in her New York City apartment to closely resemble Tibetan Buddhist shrines she encountered in her travels. All of the objects – scroll paintings as well as sculptures of buddhas, bodhisattavas, tantric deities, female deities, wrathful deities and teachers – have been arranged on traditional Tibetan furniture and according to the hierarchy they assume in Tibetan Buddhist practices.

Discussion question: On the central altar there is a sculpture made of silver, about two feet high. Who does it represent? Why would this figure have been placed in the middle of the altar?

Discussion response: This sculpture represents Buddha Shakyamuni in the earth-touching mudra, as seen in the earlier sculpture of the Buddha. Unlike the other sculptures in the shrine, this one was made from silver repoussé (hammered metal) and still retains its handsome base and beautiful flower mandorla background behind the Buddha (for more information, refer to A Shrine for Tibet, p. 71).

Exploratory Discussion: Stand quietly in front of the Shrine Room for at least one minute. Describe how the space makes you feel. How was the space designed to help you feel that way?

Resources for Further Learning

Web Resources

Gateway to Himalayan Art//Explore exhibition resources to further discover the principal concepts of Himalayan art through interactive multi-media and didactic materials.

The Rubin Museum of Art//Explore Multimedia resources and videos to find out about present and upcoming exhibition and programs at the Rubin Museum of Art.

Explore Art// Journey behind works of Himalayan art on this interactive site, revealing the stories, ideas and beliefs that inspired them. The site also lets visitors consider how peoples of other culture have expressed ideas on similar issues through their own artistic traditions.

Himalayan Art Resources//Search a virtual museum of documented Himalayan art that includes high-resolution images, essays, articles, thematic collections, bibliographies, and activities for children.

Treasury of Lives: Biographies of Himalayan Buddhist Masters//Browse biographies and portraits of Tibetan Buddhist and Bon masters by religious tradition, geography, community, and historic period.

Recommended Readings

- Beer, R. The Handbook of Tibetan Buddhist Symbols. Boston: Shambhala, 2003.

- Eck, D. Darśan: Seeing the Divine Image in India. New York: Columbia University Press, 1998.

- Eliade, M. Yoga: Immortality and Freedom. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003.

- Jackson, D. & J. Jackson. Tibetan Thangka Painting: Methods and Materials. Ithaca, N.Y.: Snow Lion Publications, 2006.

- Laird, T. The Story of Tibet: Conversations with the Dalai Lama. New York: Gove Press, 2006.

- Leidy, D. P. “The Buddha Image: 2nd to 7th Century,” The Art of Buddhism: An Introduction to its Meaning and History. Boston: Shambhala, 2008: 31-55.

- Lopez, D.S. Editor. Buddhism in Practice. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995.

- Powers, J. Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism. New York: Snow Lion Publications, 2007.

- Rhie, M. & R. Thurman. A Shrine for Tibet: The Alice S. Kandell Collection. New York: Tibet House US, 2009. Strong,

- Strong, J.S. The Experience of Buddhism. Belmont, C.A.: Wadsworth, 1995.

- Trungpa, C. Cutting Through Spiritual Materialism. Boston: Shambhala, 2002.